Our correspondance,

Barendra Tripura cannot afford the 20-odd-kilometre ride on 'chandergari', ramshackle jeeps turned into public transports that meander through the hilly terrain with more passengers and goods than they ought to carry, to the Massalong bazaar to buy a month's provisions for his family.

Once every month, the 55-year old starts from his house in the remote hills of Rangamati for the bazaar very early in the morning. He walks 40-plus kilometres to the bazaar and back to buy rice, salt, kerosene and vegetables for his four-member family.

On his latest trip to the bazaar, he had Tk 200 to buy provisions for the family, which translates into 83 paisa per person per day.

'I could manage only Tk 200, that too after two months. If I take chandergari, half of it will be spent on the fare,' said Barendra, as he walked through Konglak, a hill top locality more than 2,200 feet above the sea level, on his way to the Massalong bazaar on February 7.

Barendra, who has recently migrated from the Toi Choi mauza to Natunbari High School para (neighbourhood), is one of many internally displaced people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts who have virtually no social and economic security.

Like many others, he was forced to leave his ancestral home in Khagrachari because of the decades-long armed conflict in the hill tracts.

Internal displacement in the hill tracts started with the construction of the Kaptai dam and intensified during the armed conflict, which left more than 8,500 people killed.

Forced eviction, atrocities during the conflict between the government and the rebels, confiscation of land to establish military camps, population transfer programme, clashes between Bengali settlers and minority ethnic groups have also compelled many hill people to flee their homesteads.

Repatriation and rehabilitation of refugees was started with the signing of an agreement between the government and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samiti, bringing an end to the insurgency in late 1997, paving ways for resettlement of the displaced people.

But the problem remained thanks to inefficacy of two bodies formed to resolve the problems. The task force to rehabilitate the displaced people and the land reforms commission to settle land disputes have never functioned effectively even after 10 years of signing of the deal.

A large number of displaced people still live in reserved forest areas in the deep interior of Rangamati and Khagrachhari. Most of the refugees, repatriated from neighbouring India, live in makeshift camps housed at different government institutions in the districts with little food aid from the government.

There has been no charity for the internally displaced ones. They lack food, water, medical treatment, education, sanitation and other amenities, forcing them to continuous habitat shift from one place to other in search for better livelihood supports. Additionally, they face eviction threat from forest officials on a regular basis.

Neither the district administration nor the taskforce on CHT refugee has correct statistics on the number of displaced people, although the government spends a significant amount of money on the refugees' cause.

In the last 20 years, Tk 1,100 crore was spent from the public exchequer on the refugees, the deputy commissioner of Khagrachari, Shahadat Hossain, said.

Asked about the condition of the internally displaced persons, the chairman of the taskforce, Samiran Dewan, told New Age that a list of displaced people was prepared. 'But not all displaced people were accommodated in it.'

The list stirred a controversy as Bengalis from the plains were also included it, he added.

The hill leaders opposed inclusion of Bengalis settlers in the list, almost stalling the rehabilitation process.

'We had a series of dialogues over the matter but failed to come to any conclusion,' Samiran said.

He added that the taskforce is now tasked with distribution of rations among 12,222 families, including 90,208 from indigenous communities. Official estimates say between 500,000 and 550,000 people were displaced due to the conflict.

According to available statistics, some 5,100 people from 1,000 families were repatriated while the internally displaced people could not return to their original villages.

'Dithering by the government has put us on the street. We are not sure whether we'll get back our home and land,' a member of a repatriated family told New Age at Dighinala Upazila headquarters, where several hundred repatriated families took shelter on the premises of different government establishments.

He said the administration serve them with eviction notices on a regular basis.

'Where should I go…my land is still occupied by Bengali settlers with the assistance from the administration, why they [Bengali settlers] are not served notices,' the returnee, who was evicted from his home in 1986 in the wake of arson attacks by Bengali settlers.

After the military-controlled interim government came to power, the taskforce chairman claimed that it had rehabilitated 26 refugee families at Dhiginala.

However, local sources said, these families were not rehabilitated on their land. They were rehabilitated on a highland, not suitable for agricultural production.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

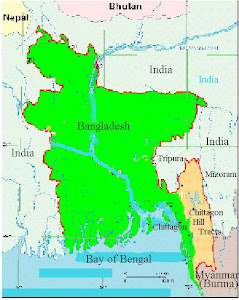

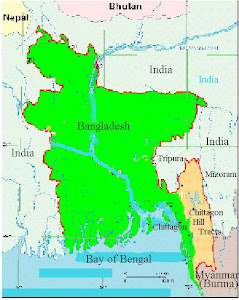

Map of Bangladesh

CHTs is number one Milliary zone in the world

Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs

The United Nation

The IJPMNA

This page provides information of the minority Indigenous Jumma Peoples in Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHTs) Bangladesh.

Contact with this please write:-ijpnusa@yahoo.com

Contact with this please write:-ijpnusa@yahoo.com

About Us

Location of Jummaland

Jumma Videos

- The BANDARBAN SADAR

- The Rowangchari

- The Ruma

- The Lama

- The Thanchi

- The Alikadom

- The Naikhkhongchari

- The RANGAMATI SADAR

- The Baghaichari

- The Langudu

- The Nanyachar

- The Barkal

- The Jurachari

- The Bilaichari

- The Kaptai

- The Rajsthali

- The Kawkhali

- The KHAGRACHARI SADAR

- The Manikchari

- The Laksmichari

- The Mahalchari

- The Matiranga

- The Ramgarh

- The Dighinala

- The Panchari

Audio & Video

Jumma Natok (Drama)

International Support

Educational Institution

Religious Organization

Buddhist Studies

Map of Bangladesh

Mission of Bangladesh

About Bangladesh

Bangali Audio Songs

Bengali News

CHTs is number one Milliary zone in the world

Online Audios

Refugee in Homeland

Jumma Picture

Blog Archive

About Me

- The Indigenous Jumma Peoples Movement in North America

- The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) region comprises three districts: Banderban , Khagrachari and Rangamati. The districts comprise seven main valleys formed by the Feni, Karnafuli, Chengi, Myani, Kassalong, Sangu and Matamuhuri rivers aid their tributaries and numerous hills, ravines and cliffs covered with dense vegetation, which are in complete contrast to most other districts of Bangladesh, which consist mainly of alluvial lands. Geographically the CHT can be divided into two broad ecological zones: (a) hill valley, (b) agricultural plains. It is surrounded by the Indian states of Tripura on the north and Mizoram on the east, Myanmar on the south and east and Chittagong district on the west.